Money left a corporate account without malware, without a breached firewall. It moved because the system accepted it. The phone in an employee’s hand behaved like an ATM that never sleeps.

Between 2015 and 2018, more than UGX 2.2 billion was drained through a bank’s online platform. Transactions were initiated, verified, and approved inside the customer’s own environment. Some instructions carried mismatched account names and numbers. The bank processed them, but the customer did not catch them in time. When the case reached court, the question was not whether fraud occurred; it was who had the last clear chance to stop it. That question put the ball squarely in both courts.

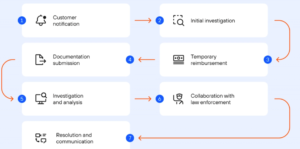

How this kind of fraud actually works

An employee logs in from a known device. No alert. A payment file is uploaded, the account number is correct, and the account name is close enough to pass a human glance. The same employee verifies the transaction. Segregation exists on paper, not in practice.

Approval is granted, and the platform allows it because the roles were never properly split. A few minutes later, funds leave the account. Proceeds are split into smaller transfers; some to bank accounts, some to mobile money, and some to intermediaries.

The trail cools, no hacking, no brute force. Just speed, familiarity, and silence. This is why mobile money and online banking fraud scale. It does not attack systems. It uses permissions.

The case that comes to mind…

In Abacus Parenteral Drugs Ltd v. Stanbic Bank (U) Ltd, decided on 9 April 2025, the High Court of Uganda refined a principle first set out in Aida Atiku v. Centenary Rural Development Bank Ltd. The Court said something many practitioners know but few contracts admit: fraud prevention in digital banking is shared. Not abstractly. Practically and contractually.

The bank argued its platform was customer-controlled. Initiation, verification, and approval sat with the client. The customer argued the bank breached its own agreement by processing instructions with obvious discrepancies, including mismatched account details. The Court agreed with both partly.

What the Court actually did

First, it confirmed the relationship is contractual. Every clause matters. If the bank agrees to reject erroneous instructions, that duty is enforceable. If the customer agrees to segregate duties and protect credentials, that duty is also enforceable.

Second, it looked at control. Who was best positioned, at each point, to stop the fraud? The customer failed to maintain basic internal controls. One officer could initiate and approve, but account activity was not monitored, and security protocols were breached. On that basis, the customer carried the larger share of blame.

But the bank was not excused. Processing transactions where the account name did not match the account number was a red flag. Failing to act on that was a breach of duty. The result was apportionment. Of the UGX 1,698,000,000 proven loss, the bank paid 20 percent. The customer carried 80 percent. That split matters. It signals how courts will think going forward.

The legal signal regulators and bankers should not miss

This decision extends the Atiku principle to corporate clients. Liability follows comparative negligence. Courts will ask a simple, uncomfortable question: who had the last clear chance to prevent the loss?

Limitation of liability clauses will not save you if they are vague. Ambiguity cuts against the drafter. If a clause does not clearly describe what is excluded and why, expect it to fail.

Most importantly, authorization is not the same as safety. A transaction can be valid in form and defective in substance. When banks ignore obvious discrepancies, the ball comes back into their court.

Technology, without romance

Banks like to say platforms are customer-controlled. That is only half true. Banks design the rails. They set tolerance levels, decide whether name-number mismatches hard-stop or soft-pass, and choose whether overrides trigger alerts or logs that no one reads.

Customers, on the other hand, control access, who has tokens, who approves, and who can act alone. When segregation collapses, the system will not rescue you.

In this case, technology did exactly what it was configured to do. That is the problem.

What corporate clients must change immediately?

One person must never initiate and approve. Not because policy says so, but because courts now expect it. Account reviews must be daily, not monthly. If you cannot explain a transaction within 24 hours, you do not control it.

Credentials are not administrative details but legal liabilities. When an employee acts with your access, the law treats it as your act unless you can prove otherwise.

If you do not know what your online banking agreement requires of you, assume it requires more than you are doing.

What banks must stop pretending

Fraud detection is not optional support; it is a contractual duty once promised. Name-number mismatches are not clerical issues. They are warning signs.

Platforms that rely entirely on customer discipline will fail in court if obvious red flags are ignored. When banks have data that customers do not, silence becomes negligence. Your phone can function like an ATM for you, or for someone who understands your routines better than you do.

Digital convenience has shifted risk, not removed it. Courts are responding by reallocating responsibility to whoever could have acted sooner. In this landscape, fraud prevention is not a slogan. It is evidence. Logs, controls, and decisions made in time.

If fraud passes through your system, the law will ask where the ball was and why you did not pick it up.

Copyright Summit Consulting Ltd 2026, All rights reserved.