Fraud doesn’t begin with bad people. It begins with pressure. With a quiet “just this once.” With a system that looks away.

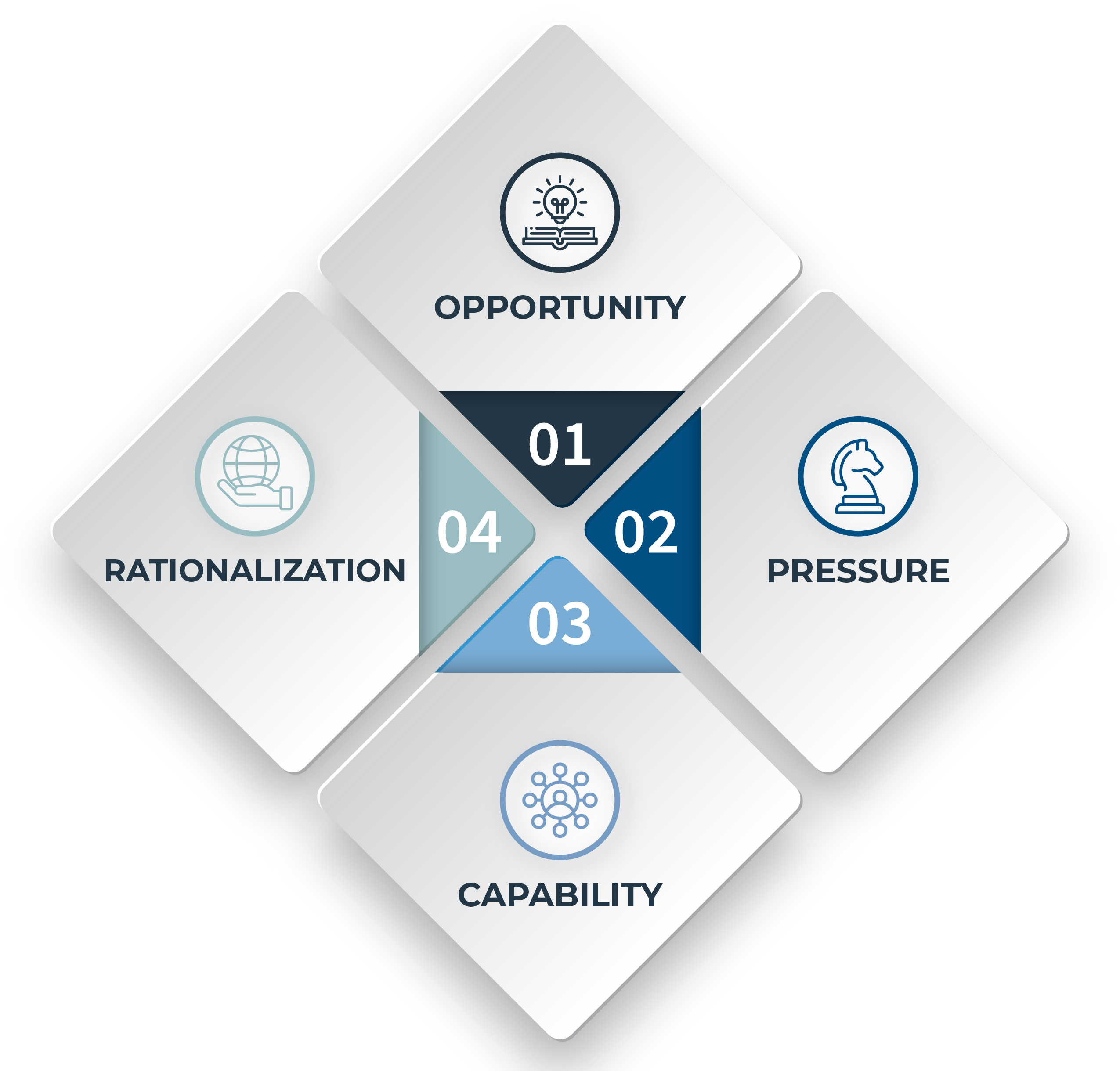

To truly understand how fraud happens, forget the Fraud Triangle. That’s kindergarten. Step up to the Fraud Diamond, a sharper, more dangerous model. It exposes not just why fraud occurs, but how the fraudster pulls it off.

There are four points to this diamond. Each one cuts deeper.

1) Motivation or pressure – the fire under the pot

I call it the boiling kettle.

Pressure builds in silence. It could be school fees, a sick parent, a gambling habit, or a toxic bonus structure. Inside, the kettle starts to boil. If there’s no ethical outlet, no support system, the steam seeks escape.

In one case in Mbale, a payroll officer altered the system to pay herself “advances.” Why? Her landlord had given a final eviction notice. Her children’s school threatened suspension. In her head, this wasn’t theft, it was survival.

Just last Saturday, I was sitting in a restaurant having a meal when a man suddenly shouted at the top of his voice:

“James, you’re a very bad person. I’m coming to evict you tomorrow. How do you live in someone’s house for over ten months without paying a single coin? I borrowed money to build that house, I pay URA, I pay KCCA, and even the man who opens the gate for you—but you sleep there, produce children, and don’t even think about paying rent? What kind of man are you? How do you even find the energy to get in the mood for producing children with that ever-accumulating rent hanging over your head?”

The man, clearly the landlord, was furious and didn’t allow the tenant to say a single word.

That, my friend, is pressure.

Now imagine that same tenant works in your company… and has access to money.

2) Opportunity – the unlocked window

A window left open at night gives easy access to intruders.

Pressure alone doesn’t cause fraud. Opportunity invites it. Weak controls. No supervision. Poor segregation of duties.

In most district local governments, fuel fraud thrives because no one reconciles fuel cards against mileage and journeys. No trackers. No oversight. So drivers inflate trips. Storekeepers divert fuel to boda riders. The window is open, and the thief doesn’t even need to break in.

3) Rationalization – the bedtime story

When a thief believes s/he’s the hero, smiles while stealing!

To sleep at night, fraudsters tell themselves stories. “They owe me.” “It’s just a loan.” “Everyone does it.” “I have worked for this company for too long, I deserve this!”

In Gulu, a hospital accountant stole UGX 75 million over 3 years. He told investigators, “I was just reclaiming all the weekends I worked without pay.” That’s not a justification—it’s a confession wrapped in entitlement.

4) Means – the master key

Before you make that spare key, make sure your locksmith has good morals.

This is what the traditional fraud triangle missed. You can have the motive or incentive or pressure, the chance or opportunity, and the excuse or rationalization but without the means, you’re still locked out.

Means are the skills, access, and tools to execute fraud. System access. Insider knowledge. Technical know-how. In Wakiso, an IT assistant cloned mobile money withdrawal codes after observing the finance team for months. No one suspected him until one day, UGX 210 million vanished from a project account.

The complete diamond motive, opportunity, rationalization, and means.

If you want to stop fraud, don’t just audit. Don’t just preach ethics. Break the diamond.

- Remove the pressure by offering support. Start personal finance training, family planning talks, and staff mentorship programs.

- Shut the window by tightening the controls. Separate duties, enforce approvals, and audit surprise transactions regularly.

- Challenge the stories people tell themselves. Teach ethics through real-life case studies and promote an open, values-driven culture.

- Block the tools they need to act. Limit system access, rotate roles, and monitor user activity with alert systems.

Fraud isn’t magic. It’s mathematics. Fix the equation before it breaks you.

And now you know the formula.